Size of People in Ancient Egyptian Art Is Based on What?

Ancient Egyptian Society and Family Life

BY | Douglas J. Brewer | Emily Teeter

SESSION 1 : Union and the Family unit

(Herodotus II: 33-37) The nuclear family was the core of Egyptian society and many of the gods were even arranged into such groupings. There was tremendous pride in one's family, and lineage was traced through both the mother's and father's lines. Respect for one's parents was a cornerstone of morality, and the most fundamental duty of the eldest son (or occasionally daughter) was to care for his parents in their last days and to ensure that they received a proper burying. Countless genealogical lists signal how of import family unit ties were, however Egyptian kinship terms lacked specific words to place blood relatives across the nuclear family unit. For example, the discussion used to designate "female parent" was too used for "grandmother," and the word for "father" was the same as "grandfather"; likewise, the terms for "son," "grandson," and "nephew" (or "daughter," "granddaughter," and "niece") were identical. "Uncle" and "brother" (or "sister" and "aunt") were as well designated past the aforementioned give-and-take. To make matters even more confusing for modern scholars, the term "sister" was oft used for "wife," perhaps an indication of the strength of the bond between spouses. Union Virginity was not a necessity for wedlock; indeed, premarital sex, or any sex between unmarried people, was socially acceptable. Once married, yet, couples were expected to be sexually faithful to each other. Egyptians (except the king) were, in theory, monogamous, and many records indicate that couples expressed true affection for each other. They were highly sensual people, and a major theme of their faith was fertility and procreation. This sensuality is reflected by two New Kingdom love poems: "Your hand is in my hand, my body trembles with joy, my heart is exalted because we walk together," and "She is more beautiful than whatever other girl, she is like a star rising . . . with cute eyes for looking and sweet lips for kissing" (afterwards Lichtheim 1976: 182). Wedlock was purely a social organization that regulated belongings. Neither religious nor state doctrines entered into the wedlock and, unlike other documents that related to economical matters (such equally the so-chosen "marriage contracts"), marriages themselves were non registered. Apparently once a couple started living together, they were acknowledged to be married. As related in the story of Setne, "I was taken equally a wife to the business firm of Naneferkaptah [that night, and pharaoh] sent me a present of silver and gilt . . . He [her husband] slept with me that night and plant me pleasing. He slept with me again and again and we loved each other" (Lichtheim 1980: 128). How like is this ancient concept and construct to contemporary Western notions of spousal relationship? Divorce Although in theory divorce was an easy affair, in reality information technology was probably an undertaking complicated plenty to motivate couples to stay together, especially when holding was involved. When a adult female chose to divorce--if the divorce was uncontested--she could get out with what she had brought into the marriage plus a share (virtually one 3rd to two thirds) of the marital articulation property. 1 text (Ostracon Petrie 18), however, recounts the divorce of a adult female who abandoned her sick husband, and in the resulting judgment she was forced to renounce all their joint property. If the husband left the marriage he was liable to a fine or payment of support (coordinating to alimony), and in many cases he forfeited his share of the joint property. Egyptian women had greater freedom of choice and more than equality under social and civil law than their contemporaries in Mesopotamia or even the women of the later Greek and Roman civilizations. Her correct to initiate divorce was one of the means in which her full legal rights were manifested. Additionally, women could serve on juries, bear witness in trials, inherit existent estate, and disinherit ungrateful children. It is interesting, all the same, that in contrast to modern Western societies, gender played an increasingly important role in determining female person occupations in the upper classes than in the peasant and working classes. Women of the peasant class worked next with men in the fields; in higher levels of social club, gender roles were more entrenched, and women were more likely to remain at home while their husbands plied their crafts or worked at civil jobs. Through near of the Pharaonic Menstruation, men and women inherited equally, and from each parent separately. The eldest son often, but not always, inherited his father's chore and position (whether in workshop or temple), just to him besides savage the onerous and costly responsibleness of his parents' proper burial. Real estate generally was not divided amid heirs merely was held jointly by the family members. If a family fellow member wished to leave property to a person other than the expected heirs, a document called an imeyt-per ("that which is in the firm") would ensure the wishes of the deceased. The Egyptians appear to accept reversed the ordinary practices of flesh. Women attend markets and are employed in merchandise, while men stay at home and do the weaving! Men in Egypt carry loads on their head, women on their shoulder. Women pass water standing up, men sitting down. To ease themselves, they go indoors, simply eat outside on the streets, on the theory that what is unseemly, but necessary, should be done in private, and what is not unseemly should be done openly.

Once a fellow was well into adolescence, it was appropriate for him to seek a partner and begin his own family unit. Females were probably thought to be fix for marriage after their first menses. The marrying historic period of males was probably a trivial older, perhaps 16 to twenty years of age, because they had to get established and exist able to support a family.

The ancient Egyptian terms for marriage (meni, "to moor [a boat]," and grg pr, "to establish a business firm") convey the sense that the arrangement was most belongings. Texts indicate that the groom ofttimes gave the bride'due south family a gift, and he too gave his married woman presents. Legal texts betoken that each spouse maintained control of the belongings that they brought to the wedlock, while other holding caused during the spousal relationship was jointly held. Ideally the new couple lived in their own firm, but if that was impossible they would live with one of their parents. Because the lack of effective contraceptives and the Egyptian's traditional desire to have a large family unit, nigh women probably became pregnant soon afterward marriage. ![]()

![]()

Discussion ![]()

![]()

Compare the legal weight of matrimony amidst the aboriginal Egyptians with marriage practice in other cultures. ![]()

![]()

Although the institution of marriage was taken seriously, divorce was not uncommon. Either partner could institute divorce for fault (adultery, inability to conceive, or abuse) or no fault (incompatibility). Divorce was, no doubt, a affair of thwarting just certainly not ane of disgrace, and it was very common for divorced people to remarry.

![]()

![]()

Timeline ![]()

![]()

View a timeline of the ancient Egyptian dynasties. ![]()

![]()

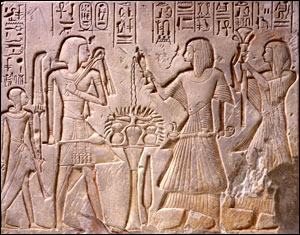

The human relationship between coitus and pregnancy was clearly recognized by the ancient Egyptians. For example, the Late Period story of Setna relates, "She lay down abreast her husband. She received [the fluid of] conception from him"; and a hymn to Khonsu relates, "the male member to beget; the female womb to conceive and increase generations in Arab republic of egypt." Although the Egyptians understood the general functions of parts of the reproductive organization, the relationships betwixt parts was sometimes unclear. For example, they knew that the testicles were involved in procreation, merely they thought the origin of semen was in the bones and that it simply passed through the testicles. Female person internal beefcake was understood even less well. Anatomical naivety can be gleaned from the fact that, although the function of the womb was understood, it was erroneously thought to be direct continued to the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, placing a clove of garlic in the vagina was supposed to test for fertility: if garlic could be detected on the breath of a adult female then she was fertile; if non, and then she was infertile. In Egyptian households of all classes, children of both sexes were valued and wanted (there is no indication that female infanticide was practiced). In addition to fertility tests, tests for pregnancy and the determination of the gender of the kid were devised. Ane test involved watering barley and emmer wheat with the urine of a hopeful mother-to-be. If the barley sprouted, the woman was significant with a male kid; if the emmer wheat germinated, she was meaning with a female child. If the urine had no effect, the woman was not significant. Though there really may be some scientific ground for this test--a pregnant woman produces a variety of hormones, some of which can induce early flowering in particular plants--there is no known relationship betwixt these plants and the conclusion of gender. The birth of a kid was a fourth dimension of slap-up joy equally well as 1 of serious concern given the loftier charge per unit of infant mortality and the stress of childbirth on the female parent. Childbirth was viewed every bit a natural phenomenon and not an illness, so aid in childbirth was commonly carried out by a midwife. Information collected from modern non-industrial societies propose that infant bloodshed in ancient Egypt was undoubtedly high. One of the best ways to maintain a healthy infant under the less-than-germ-free conditions that prevailed in ancient times was past breast-feeding. In add-on to the transfer of antibodies through female parent's milk, breast-feeding also offered protection from food-built-in diseases. Gastrointestinal disorders are common under poor sanitary conditions, and because infant immunity is reduced during weaning, children'due south susceptibility to disease increases at this time. Indirect evidence for this occurring in aboriginal Arab republic of egypt comes from a number of cemeteries where the babyhood death rate peaks at about age four, which correlates with an Egyptian child'southward introduction to solid foods. Prolonged lactation as well offered a number of heath advantages to the mother. Primarily, information technology reduces the chance of conceiving another child too soon past hormonally suppressing ovulation, which allows the female parent more time between pregnancies. The 3-year menstruation for suckling a child recommended in the "Instructions of Any" (New Kingdom) therefore struck an unconscious merely evolutionarily of import rest between the needs of procreation, the wellness of the mother, and the survival of the newborn kid. Egyptian children who successfully completed their fifth twelvemonth could more often than not look forrad to a full life, which in peasant order was well-nigh 30-three years for men and twenty-nine years for women, based on skeletal prove. Textual records indicate that for upper-class males, who were mostly better fed and performed less strenuous labor than the lower classes, life expectancy could achieve well into the sixties and seventies and sometimes even the eighties and nineties. Upper-course women as well looked forward to a longer life than women from the lower classes, but the arduous task of bearing many children resulted in a lower life expectancy compared to their male person counterparts. Dolls and toys indicate that children were allowed ample time to play, but once they matured past infancy (i.due east., were weaned) they began training for machismo. Young girls assisted their mothers with household tasks or worked with them in some capacity in the fields. Other female members of the mother's household would assistance in the care of younger siblings. Similarly, young boys followed their fathers into their occupation, first carrying out simple chores, then later working and conveying out more important tasks. Parents also familiarized their children with ideas about the globe, their religious outlook, ethical principles, and right behavior. The end of childhood appears to take been marked by the onset of menses for girls and the anniversary of circumcision for boys. That circumcision was a ritual transition from adolescence to manhood is indicated by references such as "When I was a boy, before my foreskin was removed from me." Equally far every bit is known, in the Pharaonic Period only males were circumcised, but exactly how prevalent circumcision was through club is unclear. Some uncircumcised mummies, including Rex Ahmose and perhaps Rex Amunhotep I, indicate that the do may have non been universal. Young men did not commonly cull their own careers. Herodotus and Diodorus refer explicitly to a hereditary calling in ancient Arab republic of egypt. This was not a system of rigid inheritance but an endeavor to pass on a father'due south role to his children. A son was unremarkably referred to every bit "the staff of his father's old age," designated to assist the elder in the functioning of his duties and finally to succeed him. The need for support in onetime age and to ensure inheritance made adoption quite common for childless couples; ane New Kingdom ostracon relates, "As for him who has no children, he adopts an orphan instead [to] bring him up." There are examples of a man who "adopted" his blood brother and of a woman named Nau-nakht, who had other children, who adopted and reared the freed children of her female servant because of the kindness that they showed to her. Mythically, kingship was passed from Osiris (the deceased king) to the "Living Horus" (his successor); in actuality, the eldest son of the king normally inherited the office from his father. This stela shows Rex Seti I (second from left) and his son, subsequently Ramesses II ("The Cracking"), who stands behind him. Ramesses wears his hair in a side ponytail, a style characteristic of a youth or of a special type of priest, and he carries a slender fan that was a sign of rank. This statue base of operations, which one time supported a magical healing statue, was defended by a man named Djedhor. He was Principal Guardian of the Sacred Falcon who, according to the hieroglyphic texts on this cake, cared for flocks of sacred birds. On one side of the base he appears with his daughters, on the other with his sons, an indication that he revered his daughters as much as his sons which in turn reflects the loftier status of women in ancient Arab republic of egypt. Although peasant children probably never entered any formal schooling, male person children of scribes and the higher classes entered schoolhouse at an early age. (Young girls were not formally schooled, merely because some women knew how to read and write they must have had access to a learned family unit member or a private tutor.) Though nosotros have no information about the location or organization of schools prior to the Middle Kingdom, nosotros can tell that after that time they were attached to some administrative offices, temples (specifically the Ramesseum and the Temple of Mut), and the palace. In addition to "public" schooling, groups of nobles also hired individual tutors to teach their children. Because education had not nonetheless established itself as a separate discipline, teachers were drawn from the ranks of experienced or pedagogically gifted scribes who, every bit part of their duties and to ensure the supply of future scribes, taught either in the classroom or took apprentices in their offices. Pedagogy consisted mainly of countless rote copying and recitation of texts, in club to perfect spelling and orthography. Gesso-covered boards with students' imperfect copies and their master'southward corrections adjure to this type of training. Mathematics was besides an important part of the young male'due south training. In addition, schooling included the memorization of proverbs and myths, past which pupils were educated in social propriety and religious doctrine. Not surprisingly, many of these texts stress how noble (and advantageous) the profession of scribe was: "Exist a scribe for he is in command of everything; he who works in writing is not taxed, nor does he take to pay any dues." Length of schooling differed widely. The high priest Bekenkhonsu recalls that he started school at five and attended four years followed by xi years' apprenticeship in the stables of Rex Seti I. At virtually xx he was appointed to a low level of the priesthood (wab). In some other documented case, i scribe in training was thirty years of age, just this must have been an unusual case.

Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, OIM 10507 Seti I and his son, the time to come Ramesses the Slap-up.

Limestone.

New Kingdom, Dynasty 19, Reign of Seti I, ca. 1291-1279 B.C.

Purchased in Cairo, 1919.

This relief was probably commissioned by the two priests shown at the correct to commemorate their office in the religious cult of the majestic family. Showing oneself in the presence of the rex was a great award.

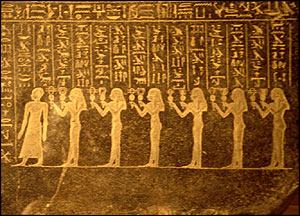

Oriental Found, University of Chicago, OIM 10589 Djedhor and his daughters.

Basalt.

Reign of Philip Arrhidaeus, ca. 323 B.C. Athribis.

Purchased in Egypt, 1919.

Aboriginal Egyptians were extremely interested in manner and its changes. This seems evident from trends seen in tomb scenes where the costumes and styles of the upper classes were soon copied by the lower classes. The well-nigh common material for clothing (both women's and men's) was linen. Considering linen is very hard to dye, most dress were off-white, and then color was added with heavy beaded collars and other jewelry. The standard apparel of women from the Erstwhile Kingdom into the New Kingdom was the sheath dress, which could exist worn strapless or with 2 broad shoulder straps. Most examples of these dresses achieve the ankles. Most sources depict women wearing impossibly tight and impractical dresses, suggesting that the representations are arcadian to emphasize the sensuality of the female trunk. The most aboriginal garment worn by men was a kilt that was made of a rectangular piece of linen cloth wrapped rather loosely around the hips, leaving the knees uncovered. As a rule, it was wrapped effectually the body from correct to left so that the border of the brim would exist in the front. The upper edge was tucked behind the tie, or girdle, that held the kilt together. This garment was the standard male attire for all classes from peasants to royalty, though the quality of the linen and the exact style varied according to one'southward purchasing power. Some of the fancier, more expensive kilts had bias-cut edges, pleated decorative panels, or fringed edges, and were made of effectively, softer linen. By late Dynasty 4 and early Dynasty 5, it became stylish to wear the kilt longer and wider or to clothing it with an inverted box pleat that appeared as an erect triangular forepart piece. Though styles changed over time, the simple kilt remained the standard garb for scribes, servants, and peasants. During the New Kingdom, when Egypt extended its political influence east into Asia, Egyptian way changed radically. With the influx of trade and ideas from the east, fashions became more varied, changed more quickly, and often took on an eastern flavor. Men and women of the upper classes, for example, wore layers of fine, well-nigh transparent kilts and long- or short sleeved shirts that tied at the neck, or draped themselves in billowing robes of fine linen that extended from neck to ankle and were drawn in at the waist by a sash. The improve examples of these garments were heavily pleated, and some were ornamented with colored ball fringe. For most of the Pharaonic Flow, women wore their pilus (or wigs) long and directly; subsequently Dynasty 18 hairstyles became more elaborate. During all periods men wore their hair brusk, simply they as well wore wigs, the style befitting the occasion. These wigs were made of homo pilus or found cobweb. Both genders wore copious amounts of perfumes and cosmetics made of ground minerals and globe pigments. Fashion statements were made with accessories such equally jewelry and ribbons. Men besides carried staffs that marked status and social form.

In the winter, the middle and upper classes wore a heavy cloak extending from cervix to ankle, which could exist wrapped around and folded or clasped in front. Depictions of such cloaks extend from Archaic to Ptolemaic times. Although sandals of blitz and reeds are known, regardless of the occasion or social grade, Egyptians plain often went barefoot.

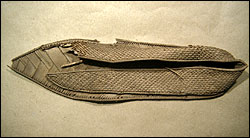

Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, OIM 7189 Shoe.

Rush.

Ptolemaic-Roman, 2nd century B.C.-2nd century A.D. Fayum, Grave H 17.

Gift of the Arab republic of egypt Exploration Fund, 1901-2.

There is much evidence for the leisure activities of the ancient Egyptians. Men engaged in physical sports, such as hunting, fishing, archery, wrestling, boxing, and stick fencing. Long-altitude races were organized to demonstrate concrete prowess, and both men and women enjoyed swimming. Board games were popular, and games boards were constructed of a number of materials: wood, stone, dirt, or elementary drawings scratched on the ground. Moves on board games were determined past throw sticks, astragali (animal anklebones), or after the late New Kingdom, cubic die that were usually marked in the same pattern used today. Ane of the most common games was senet, which was played on a board of thirty squares divided into iii rows of ten squares. Like then many other aspects of Egyptian culture, senet had a religious significance, and the game was likened to passing through the underworld. A game board in the form of a coiled snake was amid the earliest Egyptian games. Using a fix of lion-shaped and circular markers, play started at the snake's tail, which was in the class of a bird's head. The two or iv opponents raced each other to the goal located in the ophidian'due south head. Mehen was the name of the serpent deity whose coils protected the sunday god. The game of twenty squares was played past two opponents, each of whom had 5 playing pieces. Play began with the pieces placed on the undecorated areas on each side of the lath. The players moved down the side squares and up the middle of the board. Plays were adamant with throw sticks, dice, or knucklebones. Religious texts point that playing the game was likened to passing through the underworld in the quest for eternal rebirth. The "twenty square game," which originated in Sumer and was known through the entire ancient Near Due east and Republic of cyprus, was played on a rectangular lath divided into iii rows of 4, twelve, and four squares, respectively. Both senet and twenty squares were played by ii opponents. Another ancient game was mehen, played by several players on a circular board that looked like a coiled snake. The playing pieces, tiny lions and pocket-size balls, were moved from the tail of the ophidian to the goal on its head. Although this game was played in Egypt only during the Old Kingdom, it continued to be played in Cyprus for another 1,000 years. The foundation of all daily or banquet meals, regardless of social grade, was the same: bread, beer, and vegetables. The latter included leeks, onions, garlic, a number of pulses (beans, peas, lentils, etc.), and several varieties of melons. Wealthier Egyptians had more than opportunities to savour cherry meat, fowl, honey-sweetened cakes and other delicacies. Lower-class Egyptians relied on fish and fowl for most of their meat proteins. The gear up availability of wild fish and fowl made them cheap, while beef and, to a varying extent, other scarlet meats were expensive and considered by many to be a luxury. The national drinkable in ancient Arab republic of egypt was beer, and all ancient Egyptians--rich and poor, male and female--drank bang-up quantities of it. Wages were paid in grain, which was used to brand 2 staples of the Egyptian diet: breadstuff and beer. Beer was made from barley dough, then bread making and beer making are often shown together. Barley dough destined for beer making was partially baked and so crumbled into a big vat, where it was mixed with water and sometimes sweetened with appointment juice. This mixture was left to ferment, which it did quickly; the liquid was then strained into a pot that was sealed with a clay stopper. Ancient Egyptian beer had to exist drunk soon after information technology was made because it went flat very rapidly. Egyptians made a variety of beers of different strengths. Force was calculated according to how many standard measures of the liquid was fabricated from one hekat (4.54 liters) of barley; thus, beer of strength 2 was stronger than beer of strength ten. Wines in aboriginal Egypt, similar wines today, were recognized by their vintage, often identified past the name of the village, boondocks, district, or full general geographic region where it was produced. At least 14 unlike vino-producing areas existed in the Delta lonely; although the extent of these regions cannot be defined, their full general location can be identified--Upper Egyptian vintages were non every bit numerous every bit those of the Delta, only were said to be of excellent quality (eastward.g., Theban wines were known for their lightness and wholesomeness). Wines were besides known to have been produced in the oases. Wine jar labels normally specified the quality of wine, such equally "good wine," "sweet wine," "very very practiced wine," or the variety, such as pomegranate wine. It is hard to speculate nigh the sense of taste of Egyptian wine compared to modern standards. Even so, because of the climate, low acid (sweet) grapes probably predominated, which would have resulted in a sweet rather than dry wine. Alcohol content would take varied considerably from area to area and from vintage to vintage, but generally Egyptian vino would have had a lower alcohol content than modern table wines. Forth with eating and drinking went dance and vocal. Dancing seems to have been a spectator sport in which professionals performed for the guests. As a dominion, men danced with men and women with women. Singers, whether soloists or entire choruses accompanied by musical instruments, entertained guests in private homes and in the palace. During the New Kingdom, many new instruments were added to the instrumental ensemble, including minor shoulder-held harps, trumpets, lutes, oboes, and seven-stringed lyres. Trumpets were by and large restricted to the military. Egyptian lutes had a long slender neck and an elongated oval resonating sleeping room fabricated of wood or tortoise shell (the sound emitted from these instruments would have been something approximating a cross between a mandolin and the American banjo). The cylindrical drum, about 1 meter high with a leather skin laced on at each cease, was also popular during the New Kingdom; it was used both by the military and civilian population. The long oboe, played with a double reed, was introduced to Egypt from Asia Modest, and during the Graeco-Roman period, a number of instruments of Greek origin were adopted by the Egyptians, including pan-pipes and a water organ with a keyboard. Although the sound quality of the aboriginal instruments can in some cases exist recreated, no evidence exists that the Egyptians ever adult a system of musical note; thus the ancient melodies, rhythms, and keys remain unknown. Some scholars believe, however, that vestiges of the aboriginal music may be found in the music of the peoples now living in Western Desert oases, and these songs are being scrutinized for their possible origins. In contrast to the banquets of the rich and the organized meetings of the lower classes, a different type of entertainment was provided by inns and beer houses where drinking often led to singing, dancing, and gaming, and men and women were gratuitous to interact with each other. Taverns stayed open tardily into the night, and patrons drank beer in such quantities that intoxication was non uncommon. In one aboriginal text a instructor at a schoolhouse of scribes chastens a student for his dark activities: "I have heard that y'all abandoned writing and that you whirl around in pleasures, that y'all get from street to street and it reeks of beer. Beer makes him cease being a man. It causes your soul to wander . . . Now you stumble and fall upon your belly, being anointed with dirt" (Caminos 1954: 182). The streets of larger towns no doubtfulness had a number of "beer halls," and the same text as just quoted refers to the "harlots" who could be found there. Proverbs warning young men to avoid fraternization with "a adult female who has no house" indicate that some form of prostitution existed in ancient Egyptian society. For instance, the "Instructions of Ankhsheshenqy" admonish, "He who makes love to a adult female of the street will accept his bag cutting open on its side" (Lichtheim 1980: 176). During the Graeco-Roman period, brothels were known to exist near town harbors and could be identified past an erect phallus over the door, and revenue enhancement records refer to houses that were leased for the purpose of prostitution. Prostitution was not, nonetheless, associated with temples or religious cults in Egypt.

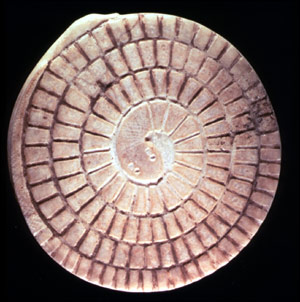

Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, OIM 16950 Serpent (Mehen) game.

Egyptian alabaster, paint.

Old Kingdom, Dynasties three-6, ca. 2750-2250 B.C.

Purchased in Arab republic of egypt, 1934.

Oriental Plant, Academy of Chicago, OIM 371 20 square game.

Acacia wood, copper.

New Kingdom, Dynasties eighteen-19, ca. 1570-1069 B.C. Akhmim?

Purchased in Egypt, 1894-5.

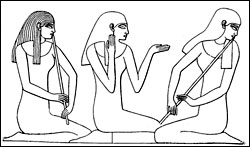

Tomb paintings indicate that banquets were a pop form of relaxation, at to the lowest degree for the upper class. At such events nutrient, alcoholic beverages, music, and dancing were common forms of entertainment. The organization of the tomb scenes may be misleading, it seems that proprieties of the times kept male and female guests seated in separate areas although men and women performed together.

Oriental Plant, University of Chicago, OIM 9819, 9820 Game markers.

Faience, ivory.

New Kingdom and after, ca. 1300-300 B.C.

Purchased, 1920.

In add-on to beer, vino was besides widely drunk. Jar labels with notations that the wine was from the "Vineyard of Rex Djet" signal that wine production was well established as early as Dynasty 1. By Dynasty 5 and 6, grapevines and wine product were common motifs in decorated tombs, and records imply that some vineyards produced considerable amounts of wine. 1 vineyard, for instance, is said to have delivered ane,200 jars of good vino and l jars of medium-quality wine in one year.

Oriental Establish, University of Chicago Nykauinpu figures: woman grinding grain (left) and winnower (correct).

It has been suggested that the effects of drinking vino were sometimes enhanced by additives. For example, tomb paintings often draw vino jars wrapped or draped in lotus flowers, suggesting that the Egyptians may have been enlightened of the narcotic qualities of blueish lotus petals when mixed with wine. There is much evidence for the excess consumption of both beer and wine, and Male monarch Menkaure (Dynasty 4) and King Amasis (Dynasty 26) figure in tales about drunkenness. Some ancient scenes are quite graphic in their delineation of over-indulgence. For instance, in the tomb of Paheri an elegant lady is shown presenting her empty cup to a servant and maxim "give me eighteen measures of wine, behold I should love [to drinkable] to drunkenness."

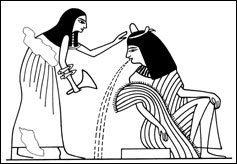

Douglas J. Brewer and Emily Teeter A woman who over-indulged (Dynasty 19).

Ancient Egyptians played a variety of musical instruments. Of the wind instruments, one of the oldest was a flute made of reed or wood, and illustrated on Predynastic pieces of broken pottery (i.eastward., sherds) as well as on a slate palette from Hierakonpolis. By the Old Kingdom, unmarried and double flutes were played. They could be side-blown (much like a modern flute), or cease-diddled (like a recorder). The flute e'er remained popular among Egyptians and it has survived to this day equally the Arabic nay and uffafa. Also popular during the Onetime Kingdom were large floor harps and diverse percussion instruments ranging from os or ivory clappers to hand-rattles (sistra) and rectangular or round frame drums. Drums of all sizes were played using fingers and hands; sticks or batons were manifestly not used.

Oriental Institute, University of Chicago Musicians entertain at a banquet (Dynasty 18).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Douglas J. Brewer

Douglas J. Brewer is professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois, Urbana, and director of the Spurlock Museum. He has written 4 books and numerous articles on Egypt, and has spent eighteen years involved in field projects in Egypt, including inquiry on the natural history of the Eastern Desert, the Palaeolithic / Neolithic transition in the Fayum, and excavations concerned with the Predynastic and Dynastic culture of the Nile Valley.

Almost THE Writer

Emily Teeter

Emily Teeter is research associate and curator of aboriginal Egyptian and Nubian antiquities at the Oriental Plant Museum, University of Chicago. She is the author of a wide variety of books and scholarly manufactures almost Egyptian religion and history, and has participated in expeditions in Giza, Luxor, and Alexandria.

COPYRIGHT This seminar is extracted from Affiliate vii of

Source: https://fathom.lib.uchicago.edu/2/21701778/

0 Response to "Size of People in Ancient Egyptian Art Is Based on What?"

Post a Comment