What Was the Biggest Problem With the First Wave of Colonization (to 1800)?

American colonial history belongs to what scholars call the early modern period. Equally such, it is part of a bridge between markedly unlike eras in the history of the western globe. On its far side lies the long stretch nosotros call the Centre Ages (or the "medieval menstruum"), on its nigh ane the rise of much we connect with modernity. It holds the root of modern science (epitomized past Sir Isaac Newton), of modern political thought (Thomas Hobbes, John Locke), of modernistic capitalism (the kickoff large articulation-stock corporations, including some which financed transatlantic "discovery"), of mod state germination ("nations," roughly as we understand the term today), of urbanization (most particularly, London and Paris, but also colonial cities such equally New York, Philadelphia, and Boston), and even of what scholars now refer to as "proto-industrialization" (the earliest factory-style modes of production). However for the great mass of European—and American—humanity, the flavor of life at ground level remained highly traditional, including an almost exclusive reliance on subsistence agriculture; immersion in small-scale-scale, contiguous patterns of social life; and a code of behavior shaped past historic period-quondam religious beliefs and folk nostrums.

The colonization by Europeans of the two peachy American continents expressed both sides of the span. Its animating source was the clash and competition of European empires—a distinctly modernistic chemical element. Yet the motivation for such effort too involved extending Christianity to "heathen lands," and locating rich sources of golden and other precious metals—twin ideas of ancient provenance.

The Peopling of Due north America

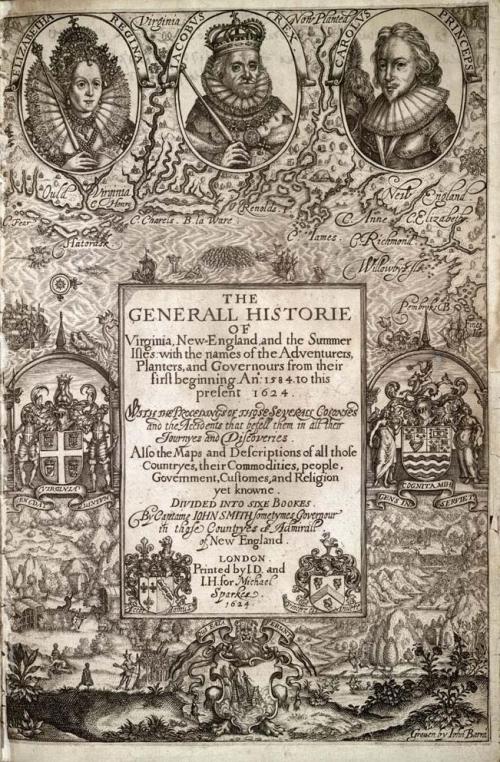

Portugal and Spain, having launched the then-called Age of Discovery at the end of the fifteenth century, laid claim to most of what is today Key and South America. The British, and others from northern Europe, were latecomers to the imperial contest. As a result, their entry, kickoff around 1600, was channeled toward what was left—importantly, the Caribbean islands and the cold, obviously hostile and frightening, coastline of North America.

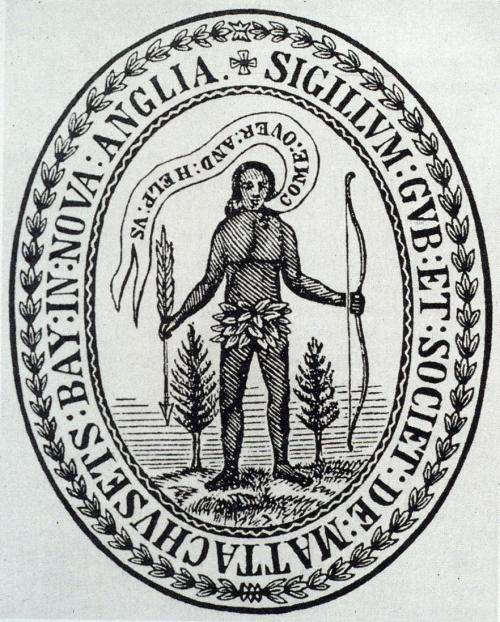

At first, their plans mirrored those of the Castilian and Portuguese. For example, the Puritan founders of Massachusetts were strongly bent on converting native "savages"—hence their adoption of an official seal with the image of an unclothed Indian proverb, "Come Over and Assist Usa." Meanwhile, the first settlers of the region around Chesapeake Bay, starting with Jamestown, Virginia, and its environment, looked more toward material gain; when Captain John Smith arrived there, he found them aimlessly searching for "golden, golden, gilt."

At first, their plans mirrored those of the Castilian and Portuguese. For example, the Puritan founders of Massachusetts were strongly bent on converting native "savages"—hence their adoption of an official seal with the image of an unclothed Indian proverb, "Come Over and Assist Usa." Meanwhile, the first settlers of the region around Chesapeake Bay, starting with Jamestown, Virginia, and its environment, looked more toward material gain; when Captain John Smith arrived there, he found them aimlessly searching for "golden, golden, gilt."

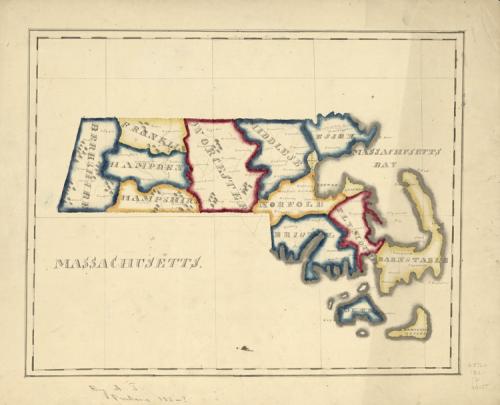

These contrasting interests would shape the development of the ii earliest British colonies for several successive generations. Massachusetts—begun at Boston in 1630, post-obit a beachhead made a decade before by the "Pilgrims" at Plymouth—retained a deeply religious orientation through about of the colonial era. Its compact towns and villages were organized effectually largely democratic "Congregational" churches; ministers played a cardinal part in the local culture; and Protestant moral strictures framed many aspects of everyday life.  Farming was the focus of productive attempt, and most of what was raised went straight to household kitchens and dinner tables. To exist sure, after about 1660 a growing class of merchants would create new lines of private enterprise, some of them extremely far-flung, while attaining high levels of wealth and developing a genteel lifestyle to match. This trend, which would not reach its apex until well into the eighteenth century, is nicely encapsulated in the phrase "from Puritan to Yankee."

Farming was the focus of productive attempt, and most of what was raised went straight to household kitchens and dinner tables. To exist sure, after about 1660 a growing class of merchants would create new lines of private enterprise, some of them extremely far-flung, while attaining high levels of wealth and developing a genteel lifestyle to match. This trend, which would not reach its apex until well into the eighteenth century, is nicely encapsulated in the phrase "from Puritan to Yankee."

Virginia, founded in 1607, was from the starting time a cog in the commercial arrangement of empire. Having failed in their quest for gold, and besides in their attempts to heighten silk, citrus products, and other potentially lucrative cash crops, Virginians turned after 1620 to intensive tobacco-cultivation. The aforementioned was true of those who founded Maryland, effectually 1635, as a refuge for Catholics fleeing the ascent pressure of Puritanism in old England. This focus lay behind the distinctive settlement design of the Chesapeake colonies—where numerous, more or less isolated, "plantations" lay stretched out forth rivers and ridgelines, with little in the way of village-style contact amid them.

Tobacco exhausted soil fertility and then speedily that individual planters felt obliged to engross large quantities of land merely in society to maintain consistent levels of product; when, after a few years, one field would no longer conduct a good ingather, cultivation was moved to others. Moreover, the same planters needed ready access to the ships that would behave their harvest to market; hence a host of niggling wharves and docks sprouted at intervals along the shoreline. Both factors—crop and marketing requirements—worked to disperse settler populations across a broad area of coastal and interior land (the Tidewater and the Piedmont, in local parlance).

Tobacco exhausted soil fertility and then speedily that individual planters felt obliged to engross large quantities of land merely in society to maintain consistent levels of product; when, after a few years, one field would no longer conduct a good ingather, cultivation was moved to others. Moreover, the same planters needed ready access to the ships that would behave their harvest to market; hence a host of niggling wharves and docks sprouted at intervals along the shoreline. Both factors—crop and marketing requirements—worked to disperse settler populations across a broad area of coastal and interior land (the Tidewater and the Piedmont, in local parlance).

In the concurrently, other European groups were joining the settlement process: the French in what is now Canada, the Dutch in New Netherlands (founded in 1626 and Anglicized four decades later, with its proper name changed to New York), scattered bands of Finns and Swedes along the mid-Atlantic coast (in the 1630s and '40s), the Spanish in Florida (as early as 1565) and besides in the far southwest (today'south New Mexico; 1607). Eventually, all except the minor Spanish outposts would be absorbed into a unmarried, English-controlled sphere of colonization.

At that place would be boosted English settlements as well. Thus several new settlements spun off from Massachusetts: Connecticut (1636); Rhode Island (1644); and New Hampshire (1679). Further down the declension came New Jersey (1670s); Pennsylvania, founded (1681) by English Quakers just thereafter populated largely by German immigrants (misnamed the "Pennsylvania Dutch"); Delaware (1704); Carolina (1663, later to be divided into two colonies, North and S); and Georgia (1732). Considered equally a whole, English men and women constituted more than ninety% of seventeenth-century colonists. Simply the following century would bring an extraordinary shift toward multiethnic, multicultural diversity, as Germans, Scots-Irish, and, most peculiarly, Africans arrived in increasingly large numbers. By the fourth dimension of the American Revolution, scarcely half the population could claim descent from "English stock."

Of course, there were too Indians, the country's original occupants and birth-right stakeholders. This grouping—perhaps 10 meg potent, continent-broad, when the first European settlers stepped ashore—would play an ambivalent part in colonization. On the ane hand, Indians often served as helpers and teachers of the struggling, sometimes overmatched, newcomers. (For example: Squanto really did bear witness the Pilgrims how to establish corn, just as fable declares.) On the other, Indians were quick to realize the threat posed past settlement to their lives and livelihoods. Thus, as early as 1622 in Virginia—and so in many other locations throughout the residual of the colonial era—"Indian wars" would shed the blood and despoil the lands of both sides. Indians won some of the battles, but not the ones that counted most. Moreover, their losses in wartime were hugely compounded by their vulnerability to epidemic diseases carried from overseas in the boats and bodies of the colonizers; past the 1700s their numbers had been reduced by a factor of ten. (No less was truthful in many parts of Portuguese and Spanish America; there, besides, disease combined with warfare to produce a staggering demographic catastrophe.)

The Settlement Process

At the get-go the settlers faced stark odds of survival. They arrived, in many cases, weakened past illness or sheer fatigue after their long sea journey. The supplies they brought were barely enough to last through their first months ashore. Their hopes for profitable trade would take years, if not decades, to realize. And their unfamiliarity with the New World environment placed them at an immediate, beyond-the-boards, disadvantage.

Indeed, most everything they encountered seemed foreign and puzzling. Most of them had no prior experience of a wooded landscape. The forests of their homeland had largely disappeared many years earlier—hence the American "wilderness" was bound to strike them as darkly menacing. Nor were they much familiar with human difference (people of different race, different civilisation, different linguistic communication); in this regard, as well, they would undergo a severe jolt upon encountering the native population.

In short, they had to suffer psychological stress besides every bit physical privation. Some gave up: retreated into private despair, failed to look after themselves, and died, every bit 1 study put it, "of melancholy." But almost managed to cope, by adjusting their lives equally all-time they could—and simply hanging on. Fortunately, the "starving times" they knew in the firsthand aftermath of arrival did non, more often than not, recur; inside a few years, and given occasional (and invaluable) assist by Indian neighbors, they were able to sustain themselves.

In short, they had to suffer psychological stress besides every bit physical privation. Some gave up: retreated into private despair, failed to look after themselves, and died, every bit 1 study put it, "of melancholy." But almost managed to cope, by adjusting their lives equally all-time they could—and simply hanging on. Fortunately, the "starving times" they knew in the firsthand aftermath of arrival did non, more often than not, recur; inside a few years, and given occasional (and invaluable) assist by Indian neighbors, they were able to sustain themselves.

Meanwhile, as well, they sought to overcome the unnerving strangeness of the land by remaking information technology in the image of home; at every indicate they sought to replicate English ways. The very names they gave their surroundings expressed this impulse: Boston, Cambridge, Exeter, Portsmouth, Northumberland, Middlesex, and many others, all transferred from places they remembered and cherished in the mother state. (There were also some to which the modifier "new" would be directly fastened: for example, New Bedford, New Hampshire, New Kent, New Brunswick, not to mention New England itself.) All this was part of convincing themselves that they had non lost their essential, long-treasured identity equally English. It was, in effect, a strategy of denial; and, for the most office, it worked.

Developing the Land

At the core of colonization, throughout the seventeenth century and on into the eighteenth, lay a development problem—or, in their own words, the problem of transforming a "wild" countryside into a "pleasant garden." State and other resource were present in dandy abundance (especially whenever and wherever Indians were not institute continuing in the way). The claiming was to catechumen these into suitably finished "goods," whether for immediate consumption or for auction in domestic and foreign markets.

The sheer scale of it was enormous. Forests must be cleared, soil prepared for cultivation, housing constructed (along with barns and other outbuildings), roadways, fences and walls lined out, boats and wagons prepared for use in send, tools and effects fashioned from whatever lay at hand. Who would do all this work? Under what conditions and with what inducements? In fact, the puddle of readily available workers was dwarfed by the size of the task; the development trouble was, first and foremost, a problem of labor scarcity.

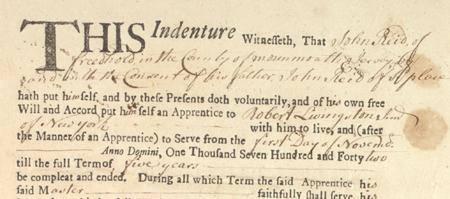

It was the same everywhere just the responses varied widely. In the Chesapeake region, the master response during the offset several decades was indentured servitude: in brusque, the contracting of generally indigent young men and women to work for a item "master" for periods of upwards to seven years. (After that he or she would become "free" and independent.) In the Carolina country, somewhat afterwards, the response would be slavery: the use, and ownership, of African bondsmen imported en masse in transoceanic tradeships. Many of the slaves in the first contingent came from those parts of Due west Africa where rice-growing was important; hence they were in a fortuitously good position to assist—or even to instruct—their owners, as Carolina adult its ain rice-based economic system. In New Netherlands/New York, a major response was tenancy: the parceling out of small plots, inside the estates of large landholders, to renters on a long-term basis. In the middle colonies of Pennsylvania and New Jersey, the response was a combination of tenancy and servitude. To be sure nearly everywhere landowners and their families added their personal efforts to the mix. In New England, nevertheless, that was near the whole story. Defective a cash crop, New Englanders did not take the actual or potential resources to invest in any form of bound labor. Instead, they did the piece of work themselves—with each household making full use of its own members, especially grown sons. (This could mean delaying the historic period of marriage, and thus of personal independence, until the late twenties or older.)

Notably, all these responses to labor scarcity, save the concluding one, involved some degree of unfreedom; and fifty-fifty New England's family-based piece of work-force was beholden to crumbling patriarchs who controlled inheritance. Accept jump labor out of the picture, and colonial development would have proceeded very differently—more than slowly, less profitably for those in charge, and with much less strain and suffering for the laborers themselves. In this regard the colonies stood in marked contrast to Europe, especially England, where a free-labor market was speedily maturing.

Even at its best, the colonial labor system brutal short. Simply put, there often weren't plenty workers to do the task correct; thus, at an everyday level, productive arrangements showed a certain sloppiness. Chesapeake planters, for instance, were notoriously careless with their lands and livestock; English visitors deplored their neglect of draining and manuring their fields, and their willingness to let cattle run complimentary in the wood. New England, despite its civilization of personal discipline and "steady habits," did niggling meliorate; outsiders often commented on the scruffy, untidy look of the countryside. Local records from the region (and elsewhere, as well) are full of notations almost fences that fell down leaving pigs to roam costless in nearby vegetable plots, sheep that were lost because of negligent herding, animate being hides that were tossed out to fester by the wayside instead of beingness sent to a tannery for processing into leather, bridges that collapsed because of inadequate maintenance, houses that caught fire from poorly built chimneys—the complaints went on and on.

At that place were, moreover, other difficulties that worked to cramp productive effort. Capital seemed ever to exist scarce; what there was of it came largely from—and and so quickly returned to—the mother country. Cash, in detail, was difficult to come by. Thus, at the local level, most substitution of goods and services involved castling or personal credit; household business relationship books from the menstruation incorporate page after page of debts owed between neighbors. The ships that carried colonial products to market overseas were near entirely English-made and English-owned. Insurance and other financial services were in the hands of English merchants. Hard goods, like firearms, stoves, and iron cookware, were likewise obtained from England. Even vesture and other textiles might well be imports. All these factors, taken together, imposed a heavy charge on colonial producers. As a issue the colonial American economy remained deeply in the thrall of the mother land; in present-day terms, information technology was a sphere of underdevelopment.

Organizing Their Lives and Communities

A different but related set of problems involved social and political organization. At commencement, the very idea of creating new man communities in furthermost lands seemed strange and perplexing. What divers a colony? What shape should it have, and what relation to the metropole? Who would be its on-site personnel? How should information technology exist governed? These were, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, all open questions, for which the promoters and founders had somehow to observe answers. The English monarchy left them largely to their own devices, offering high-sounding charters only trivial in the manner of straight support and guidance. Some colonies were designed and funded by joint-stock operations, others by wealthy proprietors (either singly or in pocket-size groups). All were expected to exist revenue-producing. And all would supposedly be ruled, in top-downwardly fashion, by boards of officials in the female parent country.

But expectations were one matter, outcomes another. Distance and the unforeseen difficulties of life on the colonial ground threw most of these founding plans off-rail. Within a generation or ii, effective governance had migrated, along with the settlers themselves, to scattered venues across the "new" continent. In Massachusetts, in Virginia, and subsequently in New York and Pennsylvania, home-grown legislative bodies sprang into being and assumed an increasing measure of control. Indeed, the same decentralizing procedure developed even at the local level, every bit individual counties and towns took accuse of their ain affairs. This process, like the heavy reliance on unfree labor, seemed to reverse prevailing trend-lines in England—where, specially later on 1660, the governing centre (the monarchy) was gathering more and more power to itself.

But expectations were one matter, outcomes another. Distance and the unforeseen difficulties of life on the colonial ground threw most of these founding plans off-rail. Within a generation or ii, effective governance had migrated, along with the settlers themselves, to scattered venues across the "new" continent. In Massachusetts, in Virginia, and subsequently in New York and Pennsylvania, home-grown legislative bodies sprang into being and assumed an increasing measure of control. Indeed, the same decentralizing procedure developed even at the local level, every bit individual counties and towns took accuse of their ain affairs. This process, like the heavy reliance on unfree labor, seemed to reverse prevailing trend-lines in England—where, specially later on 1660, the governing centre (the monarchy) was gathering more and more power to itself.

Decentralization and local autonomy did non, still, hateful democracy in whatever modern sense. Virtually everywhere the reins of power were held by elites. This was most obviously true in the southern colonies, where a small puddle of "gentlemen" dominated the membership of canton courts, and thus controlled a wide range of both authoritative and judicial affairs. Typically, these courts would handle taxes, state titles, estate probates, poor relief, militia grooming, and many other matters of everyday business organization. New England's system of town-meeting regime offered wider scope for pop participation; leaders were chosen annually by vote, and policy was decided the same way. Still, voting itself was limited to a sure portion of townspeople—in the earliest years, church building members only (in short, a religious examination); afterward, those who exceeded a specified level on the taxation-listing (a property test). Either manner a majority might well be excluded. And since these possibilities concerned men only—nowhere in colonial America could women vote—the limiting process was finer doubled.

Still other constraints were culturally determined. The aim of voting, where and when information technology might occur, was to attain a unanimous result (a consensus); conversely, majoritarian rule—deciding policy past head-count, for and against—was disapproved. Seventeenth-century colonists had no concept of a loyal opposition; to the reverse, political opposition meant disloyalty, possibly treason. (To be sure, this attitude began to weaken in the eighteenth century, as the bodily workings of colonial politics became increasingly fragmented and factionalized.) Last but hardly least, deference was a cadre principle of political, no less than social, life. Communities were idea to consist of "superiors" and "inferiors," of the "gentle" and the "common," or the "high-built-in" and the "low." Ordinary people were closely attuned to cues emanating from their "betters," whose opinions should always deport decisive weight.

The weakest point in this system was the position of the elites themselves—non in their potency over ordinary folk, only rather in their relation to each other. The process of settlement and customs-building had created a certain openness at the topmost level. Social credentials, like family full-blooded, counted for less on this side of the ocean than on the other. And sudden opportunity—a bonanza tobacco ingather, a market success in a rapidly expanding town or county—might push button a few men far up the local wealth scale, and embolden them to claim a commensurate political role. In curt, leadership might become contested to a degree rarely seen in the more firmly established communities of the Quondam Globe.

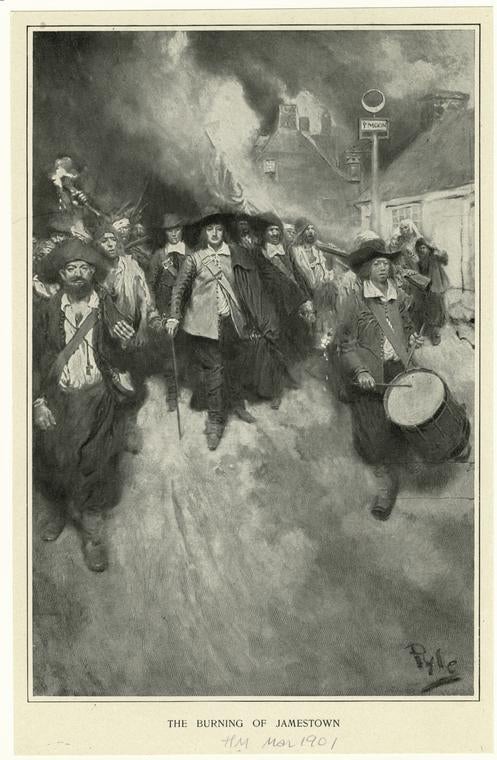

Conflict amongst rival elites peaked in a sequence of violent events during the last quarter of the seventeenth century. Bacon'due south Rebellion in Virginia (1675–1676) was a case in betoken. Though partly an "Indian war"—Virginian frontiersmen versus the native Susquehannocks—this was too a power struggle between ii of the colony'due south "great men." William Berkeley, the governor, faced a straight claiming from Nathaniel Bacon, a "high-built-in" planter and self-styled champion of the rebels. A dozen years afterward a like dynamic helped energize an uprising in New York, generally known as Leisler's Rebellion. As with the Virginia case, this event took the name of its leader, Jacob Leisler, a wealthy merchant and militia officer who chafed at his exclusion from the highest levels of the colony'south government. Both rebellions came virtually to success, but ultimately failed. In that location were like, though smaller, disturbances in Maryland and Carolina at around the aforementioned time. And in Massachusetts, the existing government was overturned in response to the so-chosen Glorious Revolution in England (the ousting in 1688 of the Stuart line of monarchs, and its replacement by King William and Queen Mary). Taken as a whole, this cluster of conflicts showed deep fault lines in the domain of leadership.

Conflict amongst rival elites peaked in a sequence of violent events during the last quarter of the seventeenth century. Bacon'due south Rebellion in Virginia (1675–1676) was a case in betoken. Though partly an "Indian war"—Virginian frontiersmen versus the native Susquehannocks—this was too a power struggle between ii of the colony'due south "great men." William Berkeley, the governor, faced a straight claiming from Nathaniel Bacon, a "high-built-in" planter and self-styled champion of the rebels. A dozen years afterward a like dynamic helped energize an uprising in New York, generally known as Leisler's Rebellion. As with the Virginia case, this event took the name of its leader, Jacob Leisler, a wealthy merchant and militia officer who chafed at his exclusion from the highest levels of the colony'south government. Both rebellions came virtually to success, but ultimately failed. In that location were like, though smaller, disturbances in Maryland and Carolina at around the aforementioned time. And in Massachusetts, the existing government was overturned in response to the so-chosen Glorious Revolution in England (the ousting in 1688 of the Stuart line of monarchs, and its replacement by King William and Queen Mary). Taken as a whole, this cluster of conflicts showed deep fault lines in the domain of leadership.

But it was a passing phase. Every bit ane century yielded to the adjacent, colonial social club attained a more solid and settled shape. The position of the leaders seemed increasingly secure, within and without their own ranks. For "common" people, besides (excluding those on the frontier, and Indians and blacks) life had become less precarious and more predictable, if still quite modest in its rewards.

North America in 1770

A bird's-eye view of the entire landscape, as of 1770, might have disclosed the following:

- Thirteen dissever English language colonies in varying states of growth and development (The French had been ousted from their hold in Canada, while the Castilian remained thinly entrenched in Florida and the southwest.)

- A nearly continuous wedge of settlement between the Atlantic shore and the Appalachian mount concatenation, extending north and south from what is today central Maine to the lower border of Georgia

- A white population of slightly more than two 1000000, with about a quarter in New England, about half in the Chesapeake and Lower Southward, and the rest in the middle colonies and then-called back-state

- An Indian population profoundly reduced in size and pushed well back from the coast, merely notwithstanding a substantial presence through several inland regions—the Iroquois in central New York, the Cherokees, Creeks, and Choctaws in the southeast

- A chop-chop growing, African-born (or derived) population of shut to half a million, well-nigh all of them slaves, and heavily full-bodied in the Chesapeake and Carolina.

And if the bird's eye were able to peek likewise into their thoughts and feelings, what else might have been discovered? What were their master goals, their most cherished values, their abiding concerns? How did they recall nearly the pregnant of their lives? The Indians and Africans are unknowable at that level, just nigh the colonists somewhat more than can be said.

Almost of them gained a measure of fulfillment in two ways. Outset, past achieving what they chosen a "competence"—a sufficiently proficient result from farming, or craft production, or, in a few cases, professional activity (ministers, doctors, midwives) to support themselves and their families as fully independent citizens. Dependence on others was abomination to them—what they wished, most of all, to avoid. And, 2d, by attaining "godliness"—if non as a clear inner reality, then at least as a matter of reputation. Good reputation was always, for these folk, a pre-eminent aim.

Their cosmology, their fashion of existence in the world, was withal securely tradition-jump and, in the literal sense, conservative. They expected always to conserve what the past had ancestral them—not to innovate, not to experiment, not to amend on the accumulated wisdom of the ages. Experience came to them in round form, indeed as an endless round of cycles: the diurnal bicycle, mean solar day followed by night; the lunar wheel, the waxing and waning of the moon; the annual bike, spring, summertime, autumn, wintertime; and—this most of import of all—the life cycle, nativity, childhood, youth, total manhood or womanhood, old age, expiry. Everything would return eventually to the point from which it had started out: in the Biblical phrasing, "ashes to ashes, and dust to dust." In this way of thinking—and of living—continuity was preferred and novelty viewed as dangerous.

Yet they, the colonial Americans, had not entirely come up round to the aforementioned starting-signal as countless generations of their forebears. And some parts of their lives were novel indeed. Without explicitly acknowledging it, they (or their parents or grandparents) had left the familiar rails in order to chart a new course. No affair how oftentimes—no matter how fervently—they declared themselves to be forever "English," they could non quite avoid seeing the arc of their difference. There was much they withal shared with their cultural kin across the ocean, withal their experience no longer fit the aforementioned pattern. They were reminded of this every time they met an Indian, walked in the "wilderness," ate cornmeal for supper, or heard the howl of a wolf at night. They were changed, inwardly as well as outwardly, and at some level they knew it.

The question and then became: Why? Was it all for good? or for sick? None could say with certainty—but this much was clear: America was dissimilar from other lands; and the lives they lived within it were infrequent, were "remarkable" (a word they often used) past the standard of their fourth dimension. Perchance, therefore, they had been marked—singled out—chosen—to fulfill some special destiny. This understanding, though still quite inchoate every bit a new era dawned, would be passed on to their descendants, would be sharpened and owned and cherished, and would inform the American story for generations yet unborn.

John Demos is the Samuel Knight Professor of History Emeritus at Yale University. Among his publications are The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America (1994), which received the Francis Parkman and Ray Allen Billington prizes in American history and was a finalist for the National Book Honor in general nonfiction, and Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England (1982), for which he received the Bancroft Prize in American History.

Source: https://ap.gilderlehrman.org/essay/colonization-and-settlement-1585%C3%A2%E2%82%AC%E2%80%9C1763

0 Response to "What Was the Biggest Problem With the First Wave of Colonization (to 1800)?"

Post a Comment